Apache Pass: Vital Communication Link Between East and West

by H. G. "Bea" Hyve

Reprinted from "INSULATORS - Crown Jewels of the Wire", October 1980, page 23

What do

the words "Apache Pass" mean to you? Probably not very much. To many

people, it is some obscure geographical location, mentioned in countless western

movies and novels. But are you aware that Apache Pass is a very real place? Did

you know that over 100 years ago it played a major role in the story of

communication in the Southwest? Yes, it is true that although the Pass lies

quiet and serene today, it was once the scene of much activity, and was a vital

communication link between East and West. And only after control of this

strategic mountain pass was wrested from the Indian and came under the

domination of the white man did regular, safe, and effective communication

develop between the extensive territory we know today as California, Arizona,

New Mexico and Texas.

Apache Pass is located in southeastern Arizona. The

Chiricahua Mountains and the Dos Cabezas range come together seem to overlap at

their bases, and the resulting narrow defile between them is Apache Pass. Zane

Grey once described it as a "tortuous crack in the hills, dark and yellow,

almost haunted." The scenery is wild and picturesque. Great spurs and

shoulders of yellowish rock jut out from above, with a variety of shrubs and

cacti growing in tangled profusion in the eroded surfaces and gaping crevices.

The Pass has a stark beauty all it's own, found nowhere else on earth. It has

been described as having "a majestic aloofness".

Although the peaks surrounding

the Pass are two to three thousand feet higher, Apache Pass itself is as high in

elevation as many mountains. The summit at the west entrance is 5,115 feet above

sea level. Traveling eastward through the Pass the road descends 515 feet to the

east entrance, a distance of about three miles. And it is this three-mile area

with which we shall concern ourselves in this story -- for it is here that most of

the history took place which, for a time, had monumental import an the

development of communication between East and West.

But how and why did

this seemingly insignificant mountain pass in a remote corner of the Southwest

become such an important communication link? For several reasons. First of all,

through its shadowy gorges lay one of the few feasible routes through the

Southwest to California. And despite the dangers which included a grade that was

steep and tortuous, it was the shortest route from the Rio Grande to Tucson. But

most important of all, Apache Spring, located near the east entrance, was the

only water for miles around. Travelers from the earliest times were compelled to

come through Apache Pass because of the life-giving water in the permanent

springs there. To go around could mean suffering from thirst for man and animal

alike.

View of Apache Pass near Fort Bowie

The earliest written records of the Apache Pass region indicate the area

was in the sole possession of the Apache Indians. They had their own

communication system consisting of smoke signals and Indian message runners.

They communicated in this way for hundreds of years. Whole ideas could be

transmitted by the smoke signals, such messages being understood surprisingly

well by the other party. Apache runners could travel up to 75 miles in one day,

and the Southwest was laced with a very efficient and dependable communication

system. Other methods were also used to communicate ideas, such as marking

trees, tying knots in the filaments of the yucca, placing stones on the ground

in a certain way, or laying a piece of buckskin over a branch of a tree or

cactus -- these and many other means were used by the Apache to convey a thought

or message to others.

In 1821 the Santa Fe Trail was opened, which soon brought

an increase of white travelers into the Southwest, many of whom traveled through

Apache Pass. At first the Apaches were friendly. There were a few incidents,

perpetrated by whites, but for the most part things went smoothly. The

California Gold Rush of 1849 brought even more white adventurers into the

region. Then came the Gadsden Purchase of 1854, which gave all of modern Arizona

south of the Gila River to the Territory of New Mexico. This placed Apache Pass

into the hands of the Americans and removed it from the Mexicans, and the area

saw an even greater increase in American travelers. Even through all of this,

the Indians usually allowed the settlers to travel through Apache Pass

unmolested, showing only curiosity for the strange people with pale skin and

"white (lighter-colored) eyes".

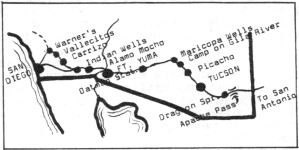

In 1857 a contract was signed by James

E. Birch for an overland mail route, and it ran through Apache Pass. This route

was also used by the San Antonio and San Diego Mail Line, and the company

boasted that the trip could be made in only 38 days. Mail was carried by

muleback over the western segment of the route, so the line acquired the name

"Jackass Mail". The schedule called for two trips each way monthly.

Not only was this the first overland mail service between San Diego and San

Antonio, but it was the first to the Pacific Coast. Mail from San Francisco and

way points came to San Diego to start the eastward trip.

Route of the "Jackass mail" from San Diego east in 1857.

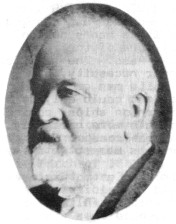

One man who

figured prominently in the development and continuation of this important

communication system in the Southwest was Silas P. St. John. A man of integrity,

courage, and vision, St. John was instrumental in building and overseeing the

construction of most of the San Antonio and San Diego Mail Line route. He was

also one of San Diego's first carriers of the Jackass Mail. The "Harbor of

the Sun" received its first mail delivery from San Antonio on August 31,

1857. On September 15 the first eastbound mail had a noisy send-off from San

Diego. A rider left at noon with his saddle bags filled. St. John took the next

leg of the journey from Carriso at 8:00 PM, and rode without a remount to Ft.

Yuma, a distance of 160 miles, in 32 hours. His route included the treacherous

Viejas and Mt. Springs grades, over 100 miles of desert, and almost 10 miles of

sand dunes. (Today I-8 follows almost exactly the route taken by St. John on

that hot September day, and takes just 3 hours in the air-conditioned comfort of

an automobile).

Silas P. St. John

(Title Insurance & Trust Co.

Historical Collection)

The following year, in September of 1858, the Butterfield

Overland Mail was subsidized by the government to carry U.S. Mail from St. Louis

to San Francisco. Mail was initially carried by mule and horseback until some

months later, when stations were established and stock was strung along the

line. At this time the era of coaches pulled by either mules or horses began.

The Butterfield Overland Mail route also traversed Apache Pass. The schedule

called for the run to be made in 25 days one way. Passenger fare was $200.

It

was also in September of 1858 that St. John was overseeing the finishing of the

roof of the stage station at Dragoon Springs (Arizona). Late one night he was

viciously attacked along with three other Americans by Mexican workers and left

for dead. They were assaulted with axes and knives. His three co-workers died,

but St. John survived, although severely wounded. He eventually lost an arm from

the injuries he suffered. St. John spent most of his life in express service and

in Indian affairs. He retired in 1913 at the age of 78, making his home in San

Diego. He died on September 15, 1919, at the age of 84. His home, located in the

Kensington area of San Diego, still stands. St. John was a true pioneer in the

field of early communication by mail.

Now that the overland mail road was

in service, emigrants to the West now had well-defined roads to follow. The fact

that there was plenty of fresh water in Apache Pass also became well known.

Travelers through the Pass grew more numerous with each passing month. More

confrontations between Apaches and white men took place, and as would naturally

follow, more misunderstandings. The lid was rattling furiously on the boiling

kettle of red and white relations in the Southwest. And it was in Apache Pass

that the lid finally blew off. And when it did, the fragile thread of

communication that owed much of its life to Apache Pass, was broken.

It was in

February 1861 that a series of unfortunate misunderstandings occurred between

the Chiricahua Apaches under their leader, Cochise, and the military. Cochise

and his people lived in and around the Apache Pass area, and had been at peace

with the Americans, allowing mail and travelers through the Pass. They even had

been supplying the mail station in the Pass with firewood.

But a young Army

lieutenant, inexperienced in Indian affairs, accused Cochise and his band of

kidnapping and robbery. The accusations were later proven false. But the

lieutenant's actions instigated a series of clashes which escalated into a

full-scale, bloody war between the two races -- a war that was to last 25 years.

But what is most important to our story is, that it was during this 25 year

period that the communication system in Apache Pass changed from Indian control

and came under the white man's control.

When this conflict began, naturally one

of the first areas to be adversely affected was Apache Pass. The need for water

made travel through the Pass a near necessity, but with Cochise on the warpath,

very few white men came through alive. Communication between East and West could

only be maintained by sending mail around the Horn on ships, coming across the

Isthmus of Panama, or by using a more northerly land route and having it come

down the west coast. But these methods took a long time and the news was

outdated by the time it reached California.

With the start of the Civil War in

the East, this area needing protection badly was left devoid of soldiers. It was

a grim situation. The citizens of Arizona felt deserted by the government, and

the Southwest was held in a vise-grip of Apache terror. It is to his credit as a

leader and a man, that from the time he went on the warpath until he made peace,

Cochise virtually brought to a halt all communication and travel not only

through Apache Pass, but in the entire surrounding area, thereby paralyzing,

communication-wise, the whole Southwest.

In June and July of 1862 several

battles took place in the Pass between Cochise and the military. These

conflicts, which included the famous Battle of Apache Pass on July 15, 1862,

made it all the more obvious that a need existed for troops to be placed in this

"most formidable of gorges". Because of these experiences, and in

order to protect the mail, construction was started on July 28, 1862, on Fort

Bowie, and two weeks later it was finished. Now for the first time in history

the white man was in full command of the spring and the route through Apache

Pass. Fort Bowie was to prove an invaluable asset; the key outpost from which

all future Apache Indian campaigns would be waged over the next 24 years.

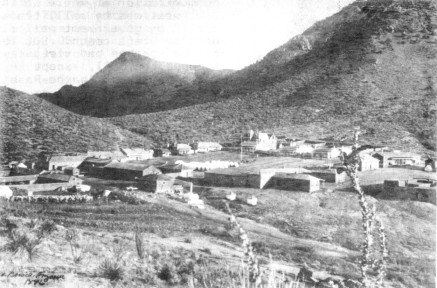

Fort

Bowie-1886

Arrow and dot (right center) mark telegraph office

(Arizona

Historical Society)

Communication was reopened for a time. Supply trains passed

through safely, but the postmaster general was reluctant to resume government

mail service via this route. So in March of 1863 it was decided to establish

semi-monthly communication by a vedette system between Tucson and New Mexico.

This system of five stations had to last for three more years, during which time

the Territory of Arizona did not have a regular mail line, government or

military. But at least with the vedette stations, these five military points

could maintain contact with each other.

In December of 1866 a post office

was established in Apache Pass, but mail carriers were still being murdered by

Apaches. Their superior knowledge of the country plus their ability to strike

and disappear quickly made them almost impossible to apprehend.

General George Crook

(Arizona Historical Society)

The war with the

Apaches was still raging when Lt. Col. George Crook of the 23rd Infantry arrived

in Tucson in June of 1871 to assume command of the Dept. of Arizona. A quiet,

mild-mannered man, Crook was honest and fair in all of his dealings with the

Indians. He was admired and respected by his men, of whom he would never ask

more than he himself was willing to give.

When Crook arrived in Arizona, the

only means of communication anywhere in the Southwest was by mail, transported

by government mail riders or stage coach. But the fierce Apaches had virtually

stopped the mail, except in the vicinity of Apache Pass and Fort Bowie, and

communication in the southern portion of the country between East and West was

almost at a complete standstill.

The idea of a telegraph line through the

territory tied been suggested as early as 1865 by the governor of Arizona,

Richard C. McCormick. (The first private line had been strung in 1865). Crook

also soon recognized a desperate need for organized communication in the area,

so that his forces could close in on the Apaches and subdue them.

In his first

Annual Report (1871) page 78, we read the following statements "Owing to

the isolated condition of this department, and the scattered distribution of its

[military] posts, the construction of a telegraph-line from California to this

country, with branches to some of the important posts, would not only be of

great service, but would be economy to the Government." It was believed

that government aid should be given to some telegraphic company for the

extension of lines to important points in the Territory. So, with the support of

such important men as the commanding general of the Army, William T. Sherman,

the plan for a telegraph system through the Southwest moved slowly ahead.

It was felt that the best connecting point on the western end of the line would

be San Diego. This city was connected to an already-operating telegraph system,

having received telegraphic communication with Los Angeles to the north in

August of 1870. Western Union agreed to build the line, headed by a veteran in

telegraph construction, James Gamble. He said he would build the line at cost,

and the Army could deduct its labor and transportation expenses from the total

cost. The details of construction were outlined, and the route was decided upon,

with San Diego as the western terminus. The line would pass east through Yuma,

Maricopa Wells, and a branch line from there to Tucson. The main line would go

to Prescott. Total distance, following wagon roads as the route from San Diego

to Tucson -- 628 miles.

Across the barren area from San Diego to Yuma would be

placed willow poles, 17 to the mile instead of 20 due to the absence of snow

along that portion of the route. They were tarred at the bottom to increase

longevity.

Cottonwood poles would be used for the route east 75 miles from Ft.

Yuma. They would cost one dollar each and be placed 20 posts to the mile. Wire

for the line would cost $30 per mile for No. 10 annealed black iron wire. Glass

insulators, $.25 each. Instruments and batteries from San Francisco would cost

about $120 for each station. Tools for the workers and incidentals added up to

about $52.95 per mile. With added expenses (payroll, etc.), the cost per mile

was $79.35. Total estimated cost, $50,311.80. Although Western Union was to

build the line, the military would operate it for reasons of economy for the

government.

Arizonans were strong in their feelings that the government should

aid in the building of the telegraph. They felt that this would help make up for

the government's running off to fight the Civil War and leaving them to the

questionable mercies of the Apaches. The bill containing the proposal and budget

for the project went to Washington, and McCormick, the governor, went with it.

After much talk and promoting, the bill became law on March 3, 1873, and the

money was appropriated.

On June 4, 1873, a Western Union employee named R. R.

Haines was hired as Superintendent of Construction. The equipment and material

began to be gathered for the new line by the Quartermaster Corps in San

Francisco. Contracts with civilian companies were made for the equipment.

Telegraph instruments, tools, insulators, and wire were purchased from the

Electrical Construction and Maintenance Company (E.C. & M. Co.) of San

Francisco. This company in turn subcontracted for the wire from the Pacific Wire

Manufacturing Company, also of that city. Both civilian and military overseers

were appointed for the various departments.

Forty tons of wire was delivered by

boat to Port Isabel (in the Gulf of California below Yuma), and then transferred

to a barge which was pulled upriver to Yuma by steamer. (In the days before

irrigation of the Imperial Valley and the building of flood-control dams, the

Colorado River at Yuma and below was much wider and deeper than it is today,

making it navigable by large vessels). Insulators, wire, and other construction

material for the route eastward from Yuma was hauled to the construction sites

by mule pack trains; the poles by wagon. Material for the western portion of the

line, from San Diego to Yuma, was delivered by boat to National City,

California, just a few miles south of San Diego.

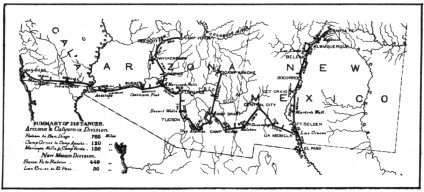

Route of the military

telegraph system

throughout the Southwest (c. 1876)

(Arizona Historical Society)

The first pole was set in the ground at San Diego on August 28, 1873, and at

Prescott on September 2. The following November 11, Prescott was joined with

Yuma. Yuma and San Diego were joined by wire on November 18, and many

congratulations were passed over the wire between Prescott and San Diego. At

last Arizona was joined communication-wise to the "outside world"! By

December Tucson was hooked up to the system. It remained now to link Tucson and

New Mexico via Fort Bowie in Apache Pass, thus completing the telegraph system

throughout the Southwest.

In 97 days there had been 540 miles of telegraph line

built, 9,820 poles set, at a cost of $47,557,97. (over $2,700.00 under the

estimated cost). It was the most important work ever undertaken in Arizona up to

that time, considerable even more so when one realizes that most of the terrain

covered included bottomless canyons, dizzying crags, snow-covered sierras, vast

deserts; an unbelievable array of all the contradictions possible in topography.

By 1874 Congress appropriated more money to extend the telegraph system to other

parts of Arizona. And on March 3, 1875, it passed a new telegraph bill covering

construction of a line connecting Santa Fe, New Mexico, with Tucson, passing

through Fort Bowie. Army troops were used to provide the labor. This was

possibly the most important link in the telegraph system along the Southwestern

border, for it included the notorious Apache Pass.

Second Lieutenant

Philip Reade was put in charge of the new line between New Mexico and Arizona in

June of 1875. He advertised in a Tucson newspaper for the purchase of poles,

asking for them to be delivered along the route, which paralleled a good wagon

road. Poles were to be of pine, oak, or cedar, 22 feet long, and not less than

eight inches in diameter at the bottom, with the bark well peeled. Not acceptable were poles of cottonwood, willow, aspen, or poplar. Poles were to be set in

the ground 3-1/2 to 4 feet deep, depending on soil conditions. Distance

between poles was to be 70 yards and 1 foot, or 25 to the mile. He then

described the method of placing the insulators on the poles and the stringing of

the wire. From the Arizona Citizen, December 4, 1875, we read:

"Insulators should be seated firmly by cutting a flat seat on the side of

the pole, and nails driven home. The top of the insulator should not project

above the top of the pole, but be flush with it. Wire should be on the same side

of all the poles. At an angle in the line the insulator must be placed on the

inside of the angle in order that the strain shall be toward the pole, and at

such angle the wire may be changed from one side of the poles to the other if

desirable; but lengths between angles must be on the same side of all the

poles." Reade went on to describe how to make the connections in the wire,

the placement of lightning rods, and the placement of supplies along the route.

He left little to the imagination, and it was clear he intended to build a

telegraph line that would endure.

Large Image (119 Kb)

The military telegraph line through Tucson

looking north at Court and Library Streets (c. 1880's)

(Bushman Collection - Arizona Historical Society)

The record is silent as to what type of

insulators were used on this portion of the line. However, complaints were later

submitted stating that the brackets for the insulators were inferior, and that

the wood screws provided with the brackets for connection to the insulators were

too small. And so were the nail holes in the bracket for attachment to the

poles. Twelve incomplete glass insulators have been found at Fort Bowie so far,

and they fall into three types.

Large Image (300 Kb)

The military telegraph line through Fort

Bowie (c. 1880's)

(National Park Service)

Six are pony insulators, CD

102. Three of these ponies are embossed with the patent dates Jan. 25, 1870 and

Jan. 14, 1879. One threadless signal-type insulator fragment was recovered,

which is probably a CD 728 or 733, and is unembossed. The last five are CD

126's. Three of these five are Brookfields. Two bear the patent dates mentioned

above, as well as 45 Cliff St., NY. The third Brookfield insulator of this type

apparently has a patent date of March 20, 1877.

By February 1876 funds ran out,

so Reade began asking citizens to provide poles. Dwellers from the key cities

and farmers living in the area donated poles and offered to haul them to the

construction sites free of charge. By April construction was resumed. By the

first week in May, 1877, that portion of the line from Santa Fe to Tucson

through Fort Bowie in Apache Pass was completed, and Arizona was now linked both

east and west by telegraphic communication. And as Crook had foreseen, the

telegraph was to help in subjugating the renegade Indian bands that ravaged the

Southwest.

Brigadier General Philip Reade

(In later years)

(National Archives)

But what did the Indians think of the telegraph? Although the

Apaches probably understood the system, they were not much different from other

tribes in other areas, who had demonstrated a superstitious respect for it. The

Apaches named the "white man's talking wire" Pesh-bi-yalti. And when

they chose, they could be very clever at disrupting the service. Among their

many tricks was cutting the wire and tying the ends together with a buck- skin

thong, making it difficult for repair crews to find the break. But for the most

part, the Indians kept their distance from Pesh-bi-yalti.

Cochise, Chiricahua Apache

chief

The great chief Cochise had made peace with the Americans in 1872.

(Cochise never allowed himself to be photographed. However, he may have looked

very much like the above drawing which was made from a bust of him, which is on

display at the Cochise Visitor Center, Willcox, Arizona). The story of

brotherhood and friendship which took place between Cochise and Tom Jeffords is

a story often told. But for the sake of our dissertation, it bears repeating.

Tom Jeffords was working as superintendent of the mails in Tucson in the middle

1860's. After losing 14 of his mail riders to the Apaches in Cochise's

territory, he decided to try and meet with the chief and ask him to allow his

mail riders to go through unmolested. Their meeting resulted in a deep

friendship between the two men that was to last until the death of Cochise. And

it was through Jeffords that President Grant's peace emissary, General Oliver 0.

Howard was able to meet with Cochise and make peace. Cochise lived only two

years after the peace, and died on June 8, 1874. He was succeeded by his son,

Taza. Although he had good intentions, Taza did not exhibit the leadership

qualities and strong personality of his father. Two years after the death of

Cochise the era of the Geronimo wars was ushered in.

Geronimo, also a Chiricahua

Apache, was a medicine man and war leader -- never a chief. Bored and restless

with the restrictions of reservation life, he and several other warriors,

including Naiche, younger son of Cochise, left the reservation for Mexico. The

year was 1876, and thus began another Apache war which was to continue for ten

more years.

By 1880 the Southern Pacific Railroad rails were laid through Bowie

Station (present day Bowie), bypassing Apache Pass and Fort Bowie by about 13

miles to the north. This spelled the end of the military telegraph in Arizona.

By 1882 the line to Fort Bowie from Fort Apache was one of very few stations

still operating in Arizona. The military telegraph was abandoned between San

Diego and Yuma also by 1882, and was replaced by the civilian (privately-owned) telegraph.

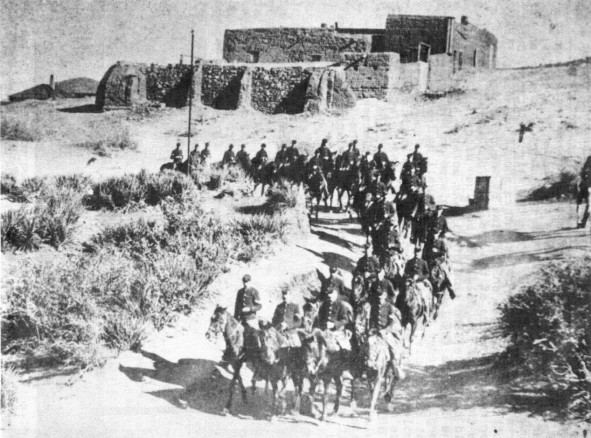

Setting up a heliograph in Arizona

(c. 1880's)

(Arizona Historical

society)

As the Geronimo campaign raged on into the mid 1880's, it soon

became apparent that a more mobile means of communication than the telegraph was

needed. An instrument was necessary that was compact enough to be packed on the

back of a mule, simple enough so that it could be set up anywhere at a moment's

notice, and yet provide instant communication. The answer was found in a simple

combination of sunlight, mirrors, and Morse code, called the heliograph, or

heliostat.

With the coming of the rails and the abandonment of the military

telegraph, the heliograph came into extensive usage. The "field"

heliograph consisted of an adjustable mirror mounted on a tripod. The heliograph

stations were usually situated on mountain tops, and operated by a team of

signal corpsmen, a sergeant and three privates. Messages called

"heliograms" were flashed from some 27 stations across the sunny skies

of New Mexico and southeastern Arizona. The mountains in Apache Pass contributed

to the importance of Fort Bowie as an important heliograph station. In fact, the

station on Bowie Peak (above Fort Bowie to the south) was the hub of all the

stations in Arizona -- here more messages were sent, received, and repeated than

at any of the other stations in the system.

The average distance between

stations was about 25 miles, although sometimes the mirror flashes could be read

as far as 50 miles away. The heliograph was introduced into the Southwestern

Indian wars by General Nelson A. Miles in May, 1886. (Miles had replaced General

George Crook as commander of the Dept. of Arizona earlier that year). These

"talking mirrors", the Army's equivalent of the Indian smoke signals,

were instrumental in helping the military to close in on Geronimo and his band.

When he surrendered to Miles through the efforts of Lt. Charles B. Gatewood in

September of 1886, the heliograph system was discontinued. Arizona was at last

free from Indian depredations.

A telephone line between Fort Bowie and Willcox

(27 miles west) was established in 1890. It replaced the telegraph as the post's

only means of rapid communication with the outside world. And in October of

1894, just before the fort was abandoned, Lt. P. 0. Lockridge and a detachment

from the post tore down the telegraph line between Fort Bowie and Willcox.

Fort

Bowie was abandoned by the Army in 1894, having seen 32 years of continuous

service as the guardian of Apache Pass. Says Richard Murray in his "History

of Fort Bowie", "Of all the posts set up ... which were involved in

the Apache struggle until the end, none served a more important purpose, nor was

more strategically located, nor had a more colorful history than Fort

Bowie."

Arizona was admitted to the Union in 1912. Roads began to be built

all throughout Arizona. About this time a graded road was constructed through

Apache Pass, following closely and generally (north of the old Butterfield Trail

blazed in the 1850's. The old trail is still visible in some places in the

Pass). The graded road is still used, although the main highway, I-10, follows

alongside the Southern Pacific tracks and passes 13 miles to the north of Apache

Pass.

In 1964 Congress authorized the making of Fort Bowie a National

Historical Site, and formal establishment took place on July 29, 1972. One can

visit the ruins of Fort Bowie by taking the Apache Pass Road south out of Bowie.

A pleasant hike of about a mile and a half will bring you to the site of the

fort.

Apache Pass -- a place of rugged beauty, mystery, and enchantment. It lies

peaceful now under the bright Arizona sun, its wild and haunting scenery hearing

only the soughing of the wind and the occasional hum of an automobile as it

threads its way over the dirt road. As one drives through Apache Pass today, it

is hard to imagine that this three mile cut between two mountain ranges was once

such a vital link in the history of communication in the Southwest.

- - - - - - - - -

When I was

young I walked all over this country, east and west, and saw no other people

than the Apaches.

After many summers I walked again and found another race of

people had come to take it. -- Cochise.

- - - - - - - - - -

I wish to give special thanks to Mr. Bill

Hoy, Ranger-in-charge at the Fort Bowie National Historic Site, for his help

with my story. He not only answered all of my questions patiently, but provided

the photo of Fort Bowie showing the military telegraph line, and was kind enough

to read my manuscript and check the accuracy of my statements.

REFERENCE SOURCES

Arnold, Elliott, Blood Brother. (1947).

Bourke, John G., On The Border With Crook. (1891).

Goodwin, G., and Basso, K., Western Apache Raiding And Warfare.

(1971).

Grey, Zane, Fighting Caravans. (1929).

Herskovitz, Robert M., Analysis

Of Material Culture From Fort Bowie, (National Historic Society, Arizona. 1975).

Lockwood, Frank C., The Apache Indians. (1938).

Murray, Richard Y., The History

Of Fort Bowie, (Master's thesis, Univ. of Arizona. 1951).

Rue, Norman L., Words

By Iron Wires Construction Of The Military Telegraph In Arizona Territory,

1873-1877, (Unpublished thesis, Univ. of Arizona. 1967).

|